BitMEX is arguably one of the most important entities in the cryptoasset industry, being by far the largest exchange of bitcoin futures contracts in the world, according to a recent synopsis of exchanges by CryptoCompare. What’s more, BitMEX’s research arm produces widely respected and read analyses germane to the industry.

This being the case, the company’s fate should be considered a matter of import for this space. In line with such thinking, this article will further explore the possibility that BitMEX could be targeted by US law enforcement entities.

What Does BitMEX Do (Wrong)?

Many people would say that BitMEX provides a great service. Crypto personality and “OG” Richard Heart is a noted fan – of the exchange’s liquidity, its very high offered leverage (up to 100 times on bitcoin futures), and what he believes is a very secure offline wallet system. “It’s a great company. Everyone else has been hacked […] everyone else has [US] exposure,” Heart says. (We’ll come back to this!)

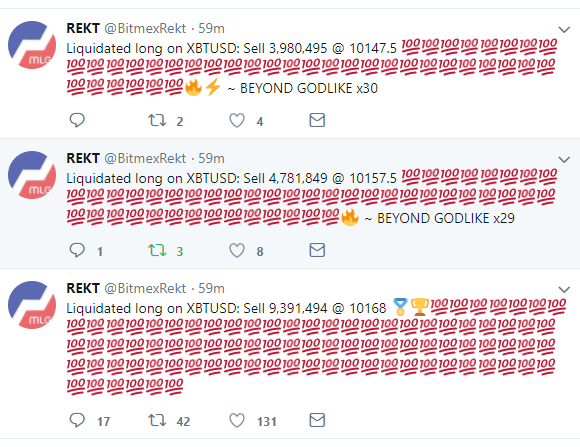

On the other hand, BitMEX has been accused of leaving its trading environment excessively precarious and prone to suffering service outages – and, critically, using those frequent blackout periods to win counter-trades against its own customers, building up a massive war chest in the form of its liquidation insurance fund. BitMEX’s CEO Arthur Hayes has specifically denied such behavior.

Whatever the nature of BitMEX’s service and motivations, it remains a viable trading platform for skilled traders and one of the keystones of cryptocurrency trading. The problem is, however, that the company sells derivative futures products, which are securities; and may in addition sell a derivative security of an underlying product (XRP) which may or may be security in the US (the jury is still out on that).

Although buying and trading such products is legal in most places, American exceptionalism strikes again: Companies are not allowed to sell such products to US citizens without registering with the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and/or the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC).

What’s more, BitMEX employs no Know-Your-Customer (KYC) or Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) checks when onboarding users. They need only provide an email address to instantly send bitcoin (and only bitcoin) to the exchange and begin trading. While many users love these features of BitMEX, such anonymous trading is an absolute no-no for many governments’ regulators and especially US regulators.

Just got my @BitMEXdotcom account terminated on suspicion of being a US Citizen. Anyone else find the timing of this odd?

The 900+ affiliates that accounted for half my income r gone going forward.

After #Unconfiscatable Conf expect prices on all services offered by me to rise. https://t.co/6bShmcdBEF— Tone Vays [@Bitcoin] (@ToneVays) November 12, 2018

For these reasons, BitMEX blocks connections from IP addresses coming from the US. However, as noted by TheBlock, US users can almost effortlessly get around this filter by using a Virtual Proxy Network (VPN). (Some browsers even have the feature built-in.)

If not for the ostensible denial of service to US customers in the form of IP blocking, BitMEX probably would have already been attacked by US regulators. Indeed, a would-be BitMEX competitor was recently shut down and its domain seized by the US FBI – and it wasn’t even a US-based company (we’ll come back to that, too).

VPN Blocking – A Must?

Many websites, companies, and even whole countries take measures to block VPN access. The battle of access and blocking connections is tit-for-tat, and there is usually some way to beat censorship. But it is quite obvious that BitMEX is not even attempting to block VPN access.

It begs the question, then: If BitMEX will not implement KYC/AML checks, are then the exchange’s paltry measures to block US customers enough to keep it out of trouble from US regulators? A somewhat recent (November) CoinDesk guest piece, penned by an expert in financial crime, considered the question of VPN blocking and if it is required to stay on regulators’ good sides.

In his opinion, “It appears unlikely that prescriptive federal VPN rules will be passed any time soon given the conservative approach taken by [US] regulators,” adding however that “if your exchange currently permits users to open multiple accounts, has no market manipulation policy or is actively encouraging market manipulation to increase your market cap rankings, VPN may only be a footnote in your eventual enforcement action.”

However, the New York Office of the Attorney General’s (OAG) September report on cryptoasset exchanges notes that in order for IP monitoring to be effective, “platforms must take reasonable steps to unmask or block customers that attempt to access their site via known VPN connections.” Within this logic, it is impossible to consider BitMEX’s measures to keep non-KYC/AML-compliant US customers off its exchange adequate.

New York is an important center of crypto-related activity in the US, currently being the only place to conduct a legal exchange of cryptocurrency and fiat money in the country, using the so-called “Bitlicense.” Therefore, the OAG’s opinion matters, and their coolness regarding VPN usage should be noted.

The case of 1Broker/1Fox

I previously mentioned BitMEX’s apparent lack of US exposure, and also alluded to a similar derivative exchange whose server was seized by the US FBI after being charged by the SEC and CFTC for illegally selling securities and futures products.

That exchange is called 1Broker/1Fox (1Broker dealt in traditional products, while 1Fox dealt with cryptoassets; they are collectively gathered under 1pool Ltd.), and it is the example case we must refer to when considering the fate of BitMEX.

1Broker/1Fox sold derivatives to both traditional assets and cryptocurrencies using an investment vehicle called a CFD, and like BitMEX accepted only bitcoin funding. Also like BitMEX, it was offshore-registered in the Marshall islands, a nation composed of tiny slivers of land clinging to the middle of the Pacific Ocean. (BitMEX is registered in Seychelles, a similar archipelago nation in the Indian Ocean known for its lax financial regulation.)

Unlike BitMEX, however, 1Broker/1Fox allowed US customers to connect and sign up without even needing a VPN. Another critical difference is that BitMEX offers no trading of traditional assets, whereas 1Broker’s CFD scheme allowed trading in traditional assets using bitcoin-backed CFDs – perhaps a thumb in the eye that US regulators could not brook.

1pool’s founder and CEO Patrick Brunner was Austrian. Combined with the offshore registration, the company had essentially no connection to the US, and – being entirely bitcoin funded – no dealing in fiat money whatsoever. And yet, both the SEC and CFTC brought charges against both the exchange and Brunner. The FBI was able, pursuant to these charges, to seize 1pool’s internet domain and shut down the website.

What Can the US Government Do to BitMEX?

Being (apparently) legally possible, how was it technically possible for the FBI to seize 1pool’s domain and take it off the internet? Could something similar happen to BitMEX if the US government decides that BitMEX’s practices are unacceptable?

This question sends us into the weeds of how the internet works. The locations of websites are both remembered and accessed by use of the Domain Name System, or DNS. Every website needs a DNS host to tell the world where it is, and every entity accessing content needs to ask a DNS provider where content is (these two sides of the DNS system, hosts and content servers need not be from the same service).

All the FBI really had to do was “ask” 1pool’s DNS provider to stop 1Broker/1Fox sending traffic to where it was supposed to go, and poof, the website is seized. The FBI then claimed the domain for itself through a different provider, sending traffic to a shell FBI website used for this sort of thing.

According to internet analytics site SecurityTrails, 1pool’s DNS provider was CloudFlare, an extremely progressive internet services company that even operates a freely available and ethically-minded private DNS lookup service.

But CloudFlare are, ultimately, a US-based company, and they do (they must) cooperate with US authorities to shut down websites using CloudFlare DNS hosting – an example of this came only days ago. A few years ago, The Pirate Bay’s use of CloudFlare as a temporary hosting service stirred up theories that it had become an FBI “honeypot.”

Who do BitMEX use? SecurityTrails shows a trail of Amazon Web Services (some report that the Ireland AWS server is being used) and AT&T Services. Both of these are US companies. Amazon was accused years ago of shutting down its service to WikiLeaks – presumably under US government pressure – after the latter infamously leaked footage of a US army attack helicopter gunning down apparently unarmed Iraqi civilians, as well as other details of the US occupation of Iraq. Amazon’s action was highly applauded by most of the US government.

Conclusions

If nothing else, these details show that BitMEX is very possibly vulnerable, both legally and technically. The flimsy blocking of US users may not placate US regulators forever. And its DNS hosting is provided by US companies, who are presumably answerable to the government and regulators there. This means that one of the financial hubs of the global cryptoasset industry – the part of it that has not been completely integrated into the traditional financial system – could be seriously exposed.